Stories from the Field reports on current issues, challenges and innovative work happening in the adult literacy and Essential Skills field throughout Alberta. The focus is on teaching and learning Reading, Writing, Numeracy and Technology.

Investigator: Sandi Loschnig sloschnig@bowvalleycollege.ca

————————————————————————————————————–

Shaping and Reshaping Teaching Practice in ESL Literacy

Published Jan 28, 2016

This two-part article examines how experienced ESL literacy practitioners in the Centre for Excellence in Immigrant and Intercultural Advancement (CEIIA) at Bow Valley College work to create transformative learning environments for their diverse learners.

Part One

The Computer Enhanced ESL Literacy Program: Embedding computer literacy in low-level classes

Norma Tersigni, Lois Heckel, and Joanne Pritchard work together in the Computer Enhanced ESL Literacy program[1], which serves learners with interrupted formal education. They talked to me about how the program works, and the advantages of working together as part of a team.

Joanne began by talking about who is in the program. “Our target audience is adult English language learners with interrupted formal education. In many cases, these learners did not have the opportunity to go to school in their home countries and now, many years later, they’re trying to acquire literacy in English. Many of the people that join our program are older adults who have been in Canada for quite a number of years. Some have worked at entry-level jobs for 20 or more years. Most are Canadian citizens, who don’t qualify for other funded programs. We also welcome many learners who are referred to us from Bow Valley College’s full-time English Language Learning (ELL) program who haven’t been able to move to the next level of the program. Our learners have very little or no literacy in their first language, little or no literacy in English, and some may even have special learning needs, such as vision and hearing disabilities. To ensure foundational learning is accessible, this Calgary Learns’ funded program has a nominal registration fee that can be waived for learners who have little to no income.”

“Many of these learners live with relatives that have already come to Canada, so they do have access to a bit of a support system. However, we also have taught learners who were homeless,” Norma added.

“Many of these learners live with relatives that have already come to Canada, so they do have access to a bit of a support system. However, we also have taught learners who were homeless,” Norma added.

The goal of the program is to help immigrant learners with interrupted formal education develop their reading, writing, and digital literacy (computer use) skills within an educational setting that that respects their learning needs and individual learning rates. The emphasis is on creating a safe environment that provides the support and time these particular learners need to develop their literacy and language skills. This class also introduces computer use in a gentle way to learners who have little or no experience using computers.[2]

The program is divided into three levels with equivalencies to the Canadian Language Benchmarks for ESL Literacy Learners. Norma teaches level one, Lois teaches level two, and Joanne teaches level three; however, the three instructors work together as a united team sharing resources and effective teaching strategies. As well, they collaborated to develop internal in-take assessment materials for the program.

Offering three levels and having small class sizes is crucial to the program’s success. Joanne explained, “Because we have three instructors in our program, offering three levels – very basic, basic, and low intermediate – allows us to meet a diverse range of learning needs. Although these groups are by no means homogeneous, we’re able to work with learners at the three different levels, in groups of only 8 to 12 learners, so we’re better able to meet their needs than if we had larger, more heterogeneous groups. Small class sizes and the three distinct levels are vital to our program’s success.”

The program runs for three 12-week terms over the year. Classes run for 3 hours on Monday, Wednesday, and Friday, and include 45 minutes of computer lab time. A unique feature of the program is that there are no set time limits. Learners move through the levels at their own pace and can remain in the program as long as they are progressing.

Lois explained, “During our program, learners make significant gains in their literacy and language development, but these gains occur in small increment steps. With time, learners develop an increased awareness of the significance of their learning achievements. I have one learner that has been in the program for quite some time. When he came into the program he was extremely quiet and didn’t ask any questions. Now, he actively engages, asking me questions, talking about his weekend, and writing in his journal.”

All three instructors emphasized the need to be flexible and responsive to the needs of learners, especially within a multi-level environment.

Norma gave an example of a lesson plan from her level one class that came from her observation of learner behaviour in the college campus. “I noticed when the learners were buying coffee that they would use a toonie or a five dollar bill, and when they got their change, they threw it in the garbage, because they didn’t know what to do with it and they didn’t know the value of it. Identifying this need created an instructional opportunity and I began to work with them on Canadian money and counting and making change. It is critical to build the financial literacy skills of ESL literacy learners – but it can be a real challenge for them. However, as a result of these lessons, I noticed that learners stopped throwing their change away.” Financial literacy, while not part of the formal curriculum in this program, is an important component of life in Canada, and ESL literacy instructors like Norma seize these real life opportunities to teach their learners the concepts of Canadian money and the value of money.

Lois spoke of the impact on practice. “I would say this program has changed my approach to teaching tremendously because I’m always thinking of new ways of doing things. I am constantly adapting my techniques to best meet needs. Working within a collaborative team allows us to share our materials and teaching approaches. I get many ideas from Norma. We try to create seamless transitions for learners from one level to the next. At point of assessment, learners move into the level best suited to their needs, but once placed, the achievement of outcomes determines movement to the next level.”

When I asked them to describe a typical day in their classrooms, the three instructors provided a good picture of the scope of the program.

Norma began. “At my level [level one], instruction needs to be very explicit. Learners benefit from routine and repetition. Because they’re non-readers, I include activities that foster metacognitive skills. For example, they have a binder with dividers, and I colour code the dividers so that, initially, they don’t have to be able to read anything – if we start out with vocabulary, I ask them to flip over the green coloured tab. So there isn’t the stress and they’re relaxed. If they’re anxious or worried about performance, they won’t learn. I have them do quite a bit of work ahead of actually working on the computers. I use a template of the keyboard they have at their desks and we practice putting website addresses in, finding letters. We practice in the classroom that way. And then I call them up one at a time to the computer at my desk and we rehearse what they’re going to do in the computer lab.”

“When we go in the computer lab, we blend our classes, so Lois [level two] and I are in the computer lab together. My learners have a role model – they see Lois’ learners are generally more proficient on the computer. It’s an opportunity for some peer tutoring because some of Lois’ learners will stop what they’re doing and help my learners,” Norma added.

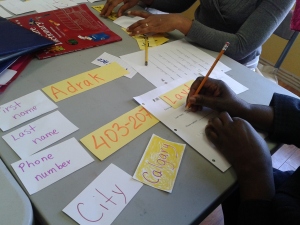

Lois described some of the level two learning activities. “We always try to incorporate authentic learning opportunities. For example, some of the learners will bring in letters that they get about their income tax or a phone bill. They require help in understanding what information is being forwarded to them. One of the goals at my level is to help learners independently complete short forms where they have to give their name, their address, their status, etc. We practice the skill of form filling. We also focus on oral/aural skill development, for example how to respond to questions about where they live, etc. We do lots of role playing. I have introduced this activity called ‘in the hot seat.’ In this activity one learner is in the hot seat and the other learners ask questions such as ‘Where do you live?’, ‘What is your address?’ This activity becomes a springboard for learners to pose new questions of their own.”

Learners in Joanne’s level [level three] are able to demonstrate higher literacy skills and are beginning to share their stories through print. “I spend considerable time at the beginning of each term with oral activities for learners to get to know each other. As we move into the term, classes often begin with several of the students reading their completed (and jointly edited) work from a previous computer class, usually just 3 to 5 sentences on a topic. As the other learners in the class listen to their classmates’ stories, they are asked to identify what their classmate had to say about the given topic. To introduce new material, I use the SMART projector in my classroom to project web-based resources such as the ESL Literacy Readers. Learners are provided with booklets that contain the same reading passages as well as activities that relate to our thematic unit to complete during  class and for homework. I try to focus on topics that are relevant to their lives in selecting our themes, and I encourage each student to express their own personal ideas in their writing. When they share their written sentences with the rest of the class, it’s their individual ideas, not something I’ve given them to type or the ideas of someone else in the class. Because of the wide-range of literacy levels, I structure each activity so that each student can work at his/her level.”

class and for homework. I try to focus on topics that are relevant to their lives in selecting our themes, and I encourage each student to express their own personal ideas in their writing. When they share their written sentences with the rest of the class, it’s their individual ideas, not something I’ve given them to type or the ideas of someone else in the class. Because of the wide-range of literacy levels, I structure each activity so that each student can work at his/her level.”

The joint learnings of the three instructors working in the program have been gathered together to inform the development of an internal program handbook. The handbook includes the learning outcomes for each level as well as suggestions for thematic units and related online and print resources. The handbook continues to be updated as these instructors shape and re-shape their teaching practice to meet evolving learner needs.

Part Two

Experienced practitioners working to create transformative learning environments

Shelley McConnell and Julia Poon have 40 years combined experience teaching in the CEIIA. I spoke to each of them about their evolving teaching practices and philosophies.

In addition to her teaching responsibilities, Shelley McConnell shares her experience and learning through professional development workshops and webinars designed for ESL literacy practitioners. She started our conversation.

“The target audience that I work with is people who didn’t go to school before in their country and have primarily lived in an oral culture. Print literacy wasn’t a part of their lives to any great extent.”

Shelley also spoke about an additional and often overlooked challenge faced by these learners. “In addition to being from oral cultures, my learners may have another challenge when adapting to life in Canada and developing literacy skills here. I would say a good number of the people I work with have not fully acquired their traditional culture to the extent that their grandmothers and great grandmothers might have. A lot of them have gone through many sudden interruptions and been displaced from elders and other chances to take part in their traditional culture. They might not have had traditional knowledge, life skills, and strategies passed down to them.”

Like all ESL literacy practitioners, Shelley believes in building on learner strengths.

“That’s why I like Decapua and Marshall’s model of a ‘Mutually Adaptive Learning Paradigm (MALP)’.The idea is to start with the channels through which people have learned in the past and then build on those strengths. You show them that those learning channels are valuable rather than liabilities. And then starting from there, you build on those learning styles and then help them adapt and develop new strategies while not necessarily giving up their old strategies either. So instructors adapt to facilitating learning in a learning style that is not necessarily their own, and learners adapt to learning through new channels.”

Shelley spoke about the need for using different approaches to teaching ESL literacy learners. “A common characteristic our learners share is the need for a very kinesthetic and hands-on approach to learning. A lot of the literature talks about developing oral language and oral language awareness first, and I think this is the case, but I think it is in conjunction with hands-on kinesthetic modelling, since this is the mode in which those from more oral cultures have been learning their whole lives. It’s very different from how I learn. I’m a very visual kind of learner, and I’ve had to adapt to teaching in a very kinesthetic, tactile, and auditory mode of learning.”

Shelley added, “We work a lot with developing concepts and strategies as well as language. When I taught mainstream ESL learners, they transferred concepts behind pieces of vocabulary directly from their language into English, so it’s relatively easy. But with these learners, you’re often teaching or deepening the concepts behind vocabulary as well as the vocabulary itself. For example, if I’m teaching the word ‘address’. For somebody who is educated and has lived in places with addresses that word has a deep concept behind it. They might know or assume that the system of how we derive ‘addresses’ in Canada might be slightly different from their country, but they would know that there is a system by which we assign or describe a location through text to another person. Whereas, ESL literacy learners might not have been exposed to this concept before, or have only a very superficial concept of the word ‘address’. They might know they have an address and may even have memorized it orally, but they don’t know what an address is used for. We help them develop the concept of what that word means in addition to teaching the language around it. I think that’s a big piece of learning for people coming into teaching ESL literacy – that we’re facilitating learners to develop or deepen concepts as well as learning the language itself.”

Shelley also emphasized the importance of teaching concepts in context as opposed to the artificially created context of a classroom.

“We’re teaching in probably the most foreign context for them – the classroom, and add to that mix trying to teach concepts completely decontextualized from the place where those concepts are lived. The approach that I always start with is having them experience concepts in real life outside the classroom, or simulate those contexts in the classroom. The learning that they have done in the past has been much contextualized. They would have learned, experienced, and used concepts in the location in which they would have been immediately relevant, practical, and useful. My approach is almost always to start with some kind of hands-on real experience and documenting that experience somehow, for example through photography, videotaping, or re-enactment, and that documentation becoming part of the content that we explore in the classroom.”

“Another thing that these learners don’t have is full print awareness. The best way that I’ve heard it described is, that when you’re reading, what you’re really doing is listening on paper or listening with your eyes, and when you’re writing, what you’re really doing is speaking with your pencil or speaking on paper. And learners don’t have that concept – that they can get information, they can listen through their eyes, or they can speak through their hands with text or pictures they create. I’m trying to help them discover that in this society we listen and speak in this different way a lot – that it is often the most common way we deliver, receive, and recall information.”

“Another thing that these learners don’t have is full print awareness. The best way that I’ve heard it described is, that when you’re reading, what you’re really doing is listening on paper or listening with your eyes, and when you’re writing, what you’re really doing is speaking with your pencil or speaking on paper. And learners don’t have that concept – that they can get information, they can listen through their eyes, or they can speak through their hands with text or pictures they create. I’m trying to help them discover that in this society we listen and speak in this different way a lot – that it is often the most common way we deliver, receive, and recall information.”

Shelley gave me an example that aptly illustrates how an ESL literacy learner can miss the use of text in his environment. “I’ve had learners who are beginning to read independently and could potentially read new words decontextualized from the support of the classroom. But they don’t know to look for text in their environment – they don’t fully know they’re constantly being communicated to in that way. I had one learner, for example, who was working as a cleaner in an office building. He came to school one day with this hand-written note, in large lettering written with a black Jiffy marker: Please clean this table. He said, ‘I just about got fired today.’ He explained it was because an executive had left this large note for him, but he hadn’t noticed it on the table in the room he was cleaning. He didn’t understand that anybody would be giving him instructions that way, so he didn’t keep his eye out for a note like that. He could read that sentence well, but didn’t know to look for it. He came to class that day with the note and asked to say something to the class. He held up the page, and said, ‘Hey everybody, did you know that Canadians talk to you like this?’ It was a ‘light bulb’ moment for him and for the other students, who assumed that bosses would always give instructions to employees orally.”

Shelley’s professional development workshops and webinars are available on the ESL Literacy Network. She also gives in-person workshops sharing her philosophies and ways of working.

Julia Poon has spent the last 30 years teaching in the CEIIA. She shared her personal experience of the shift from teaching mainstream ESL to teaching ESL literacy and how it has shaped her teaching practice.

Part of Julia’s role in the department is doing a combination of summative and formative assessment as well as an informal interview to determine where to place ESL literacy learners.

“While I do give them a reading/writing test, I’m also assessing whether or not they can follow a certain format that I’m sharing. For example, we look at a calendar to see if they can follow it. I notice whether they track from left to right. I use photos and ask them to match them with words. If they have difficulties with spatial awareness, it can be an indicator that they are ESL literacy learners. And of course we talk about their life history, school background, rural or urban – those types of things tell me a lot.”

I asked Julia how her teaching practice has changed over the years to meet the needs of these unique learners. She explained, “From my experience working with these learners, I understand that they really need to start with the concrete and not from the abstract. Everything has to be concrete, or what I call experiential learning. They need to do tasks that situate the learning in their real lives. When we focus on storytelling or developing stories, for example, the stories are told by the learners about a shared experience we have had, such as going to the zoo. Another understanding is that these learners need a lot more repetition, hearing or exposure to the same thing over and over in different ways. So I might do things like a song, chant, or story that uses the same words. I also use different media (art and music) to repeat the same vocabulary. And I use manipulatives as much as possible. Moving things around, doing things with their hands and bodies situates the learning in the physical. Kinesthetic learning is really important for these learners. Most importantly, I learned that they need time to absorb things. I learned patience.”

I asked Julia how her teaching practice has changed over the years to meet the needs of these unique learners. She explained, “From my experience working with these learners, I understand that they really need to start with the concrete and not from the abstract. Everything has to be concrete, or what I call experiential learning. They need to do tasks that situate the learning in their real lives. When we focus on storytelling or developing stories, for example, the stories are told by the learners about a shared experience we have had, such as going to the zoo. Another understanding is that these learners need a lot more repetition, hearing or exposure to the same thing over and over in different ways. So I might do things like a song, chant, or story that uses the same words. I also use different media (art and music) to repeat the same vocabulary. And I use manipulatives as much as possible. Moving things around, doing things with their hands and bodies situates the learning in the physical. Kinesthetic learning is really important for these learners. Most importantly, I learned that they need time to absorb things. I learned patience.”

Julia shared one of her more unique learning activities as an example of kinesthetic and experiential learning. “One thing I have done a few times is hold a numeracy sale, which is similar to a garage sale. I asked teachers, everyone, to donate things that they didn’t need. I got the learners in my different classes to decide the prices – that way everyone has an opportunity to price items. They also take turns being the cashier and the supervisor during the sale. The whole activity gives the learners an authentic place to practice the numeracy skills they are learning in class. The money made goes to the student emergency fund. It’s a learning activity that everyone enjoys.” Julia created a video about this activity that is shared on the ESL Literacy Network: https://esl-literacy.com/community/showcase/numeracy-sale

Julia also emphasized the need to be spontaneous and flexible in the classroom. “We can take whatever happens in the class, and create a learning moment. I think those are actually the best lessons. It’s not the ones that are planned perfectly and stick to the agenda. I don’t know if the learners will remember them in the same way. But, for instance, a learner getting stuck in the elevator, as happened one time, can become a big lesson in itself. I’ve become more spontaneous and less attached to lesson plans – although learning outcomes are still a focal point.”

For Julia, success is measured in small steps and subtle changes. She explained, “It’s those subtleties that make me feel I have made a difference. It’s the little things that I see. Like someone who might be very quiet and shy and in class they don’t want to say anything, but by the end of the term, has come out of their shell and is interacting more and has more confidence. Those are the things that I think really make the big difference to me. But those things sometimes are hard to quantify. When I see them from the beginning of term to the end of term, I notice the little differences in their personality, in the way that they approach things, in how they interact with other learners, how they adjust themselves to fit into the class routine. I think what supports them and helps make them successful in life is these other little things, like knowing how to adapt to a situation and demonstrating effective social skills.”

For Julia, success is measured in small steps and subtle changes. She explained, “It’s those subtleties that make me feel I have made a difference. It’s the little things that I see. Like someone who might be very quiet and shy and in class they don’t want to say anything, but by the end of the term, has come out of their shell and is interacting more and has more confidence. Those are the things that I think really make the big difference to me. But those things sometimes are hard to quantify. When I see them from the beginning of term to the end of term, I notice the little differences in their personality, in the way that they approach things, in how they interact with other learners, how they adjust themselves to fit into the class routine. I think what supports them and helps make them successful in life is these other little things, like knowing how to adapt to a situation and demonstrating effective social skills.”

Some final words

These ESL practitioners are creative, adaptive, and intentional, and they work hard to provide a seamless and supportive learning experience for the more vulnerable ESL literacy learners. Their responsive curriculum can change to meet learners’ requirements. Perhaps most important of all, the ESL literacy learners in these programs are supported to move forward at their own pace, measure and celebrate their progress, and support each other as they learn and practice new skills.

| In this series, ESL literacy practitioners working in the Centre for Excellence in Immigrant and Intercultural Advancement (CEIIA) at Bow Valley College shared their successes and challenges, best practices and approaches, innovations, and professional development needs. Read the other articles posted on the Bow Valley College Adult Literacy Research Institute website at Stories from the Field. |

Suggested Resources and Websites

Bigelow, Martha, and Robin Lovrien Schwarz. 2010. Adult English Language Learners with Limited Literacy. Washington, DC: National Institute for Literacy. http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED512297.pdf

Canadian Language Benchmarks: ESL for Adult Literacy Learners has as its purpose to describe the needs and abilities of adult ESL Literacy learners, and to support instructors in meeting their learning needs.

http://www.language.ca/documents/CLB_Adult_Literacy_Learners_e-version_2015.pdf

ESL Literacy Network website is an online community of practice that provides resources and information to support the professional development of ESL literacy practitioners.

https://esl-literacy.com/

Fanta-Vargenstein, Yarden, and David Chen. n.d. “Time Lapse: Cross-Cultural Transition in Cognitive and Technological Aspects – The Case of Ethiopian Adult Immigrants in Israel.” International Journal of Knowledge, Culture and Change Management 10(3): 59-76.

Mutually Adaptive Learning Paradigm® is the website of Dr. DeCapua and Dr. Marshall, who have published articles and books on MALP® which provide both theory and practice, and contain many examples of lessons and projects for all types of programs and students, including those with limited formal education.

http://malpeducation.com/resources/

Multi-lingual Minnesota has as its goal to increase access to language learning by providing an online resource center that collects and shares the many language learning activities taking place across the state of Minnesota. http://www.multilingualminnesota.org/

[1] This program is funded by Calgary Learns with funding support provided by Alberta Innovation and Advanced Education.

[2] Computer use is one of the nine essential life skills every individual needs to successfully participate in learning, work, and life as identified by the Government of Canada. The nine skills are: Reading Text, Document Use, Writing, Numeracy, Oral Communication, Thinking, Working with Others, Computer Use, and Continuous Learning. (http://skillscompetencescanada.com/en/what-are-the-nine-essential-skills/)

______________________________________________________________________________________

ESL Literacy Readers: Igniting a passion for reading in ESL literacy learners

“We do learn to read by reading”

Frank West (cited in Smith and Elley 1997)

I still remember my excitement when I learned to read. The bookmobile came to our school every two weeks and I would take out the full limit of books allowed. By the time the bookmobile returned I had read everything and was eagerly waiting to restock my stash. This early and extensive reading ignited my passion for reading and writing, a passion that still exists today.

Teacher and scholar Alan Maley researched and wrote at length about extensive reading and its benefits for English language learners. He compiled a list of characteristics of extensive reading, which includes the following:

- Students read a lot and often.

- There is a wide variety of text types and topics to choose from.

- The texts are not just interesting: they are engaging/compelling.

- Students choose what to read.

- Reading purposes focus on: pleasure, information, and general understanding.

- Reading is its own reward.

- Materials are within the language competence of the students.

- Reading is individual, and silent.

- The teacher is a role model…a reader who participates along with the students. (Maley 2009)

Simply put, extensive reading is reading a lot and reading for pleasure. The goal is “to create fluency and enjoyment in the reading process” (Clarity 2007).

Ample research evidence supports the benefits of extensive reading. It helps develop learner autonomy; provides massive and repeated exposure to language in context; increases general language competence (writing, speaking skills); develops general, world knowledge; extends, consolidates, and sustains vocabulary growth; improves writing (the more we read the better we write); and creates motivation to read more (Maley 2009).

It is clear that extensive reading would benefit adult ESL literacy learners for all these reasons. For them to begin, the first task would be finding books written at the appropriate levels for this diverse group. And that is where this story opens.

The ESL Literacy Readers Project: Developing resources for ESL literacy learners

In early 2010, Theresa Wall and Joan Bruce, ESL literacy practitioners in the Centre for Excellence in Immigrant and Intercultural Advancement (CEIIA) at Bow Valley College, embarked on an ambitious project: to substantially increase the available reading resources for adult ESL literacy learners. As practitioners they experienced frustration with the lack of suitable reading materials for their learners. And like many practitioners working in the field, they created their own materials from scratch or modified existing materials intended for mainstream ESL learners. Out of this need, an idea emerged: to develop a series of books designed specifically for adult ESL literacy learners that would be openly accessible to practitioners everywhere.

In early 2010, Theresa Wall and Joan Bruce, ESL literacy practitioners in the Centre for Excellence in Immigrant and Intercultural Advancement (CEIIA) at Bow Valley College, embarked on an ambitious project: to substantially increase the available reading resources for adult ESL literacy learners. As practitioners they experienced frustration with the lack of suitable reading materials for their learners. And like many practitioners working in the field, they created their own materials from scratch or modified existing materials intended for mainstream ESL learners. Out of this need, an idea emerged: to develop a series of books designed specifically for adult ESL literacy learners that would be openly accessible to practitioners everywhere.

The result was the ESL Literacy Readers project funded by Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada. By its end, the project created 40 readers intended to be used in conjunction with theme-based lessons for adult ESL literacy learners.

Theresa described the project’s early days. “When we started this project, there were very few materials available developed for adults who were new to reading. Our goal was to develop books for ESL literacy learners that were appropriate for adult readers. We wanted the characters to reflect the learners in our ESL literacy programs. The books would complement the settlement themes used in LINC[1] classes. We wanted to create something that instructors could use as part of a larger unit in their classroom instruction and that learners would read with support at the beginning, and independently by the end of the unit. We wanted reading to be a successful experience for ESL literacy learners. In the end, the project team wrote eleven to sixteen readers at each of the different levels from introductory to intermediate.”

“The entire team of writers and editors were ESL literacy practitioners in Bow Valley College’s ESL Literacy and Practical programs in the CEIIA. In all, there were six writers and the two of us as editors directly involved. Other CEIIA instructors supported the process by piloting the readers in their classes and offering feedback on the stories.” Theresa explained, “Instructors worked in pairs, with two teachers writing for one phase. Some instructors worked together and would meet throughout the process. After writers finished a story, they would send it for editing, where Joan and I would run the stories through all of the criteria we had developed as a team earlier in the process.”

“The entire team of writers and editors were ESL literacy practitioners in Bow Valley College’s ESL Literacy and Practical programs in the CEIIA. In all, there were six writers and the two of us as editors directly involved. Other CEIIA instructors supported the process by piloting the readers in their classes and offering feedback on the stories.” Theresa explained, “Instructors worked in pairs, with two teachers writing for one phase. Some instructors worked together and would meet throughout the process. After writers finished a story, they would send it for editing, where Joan and I would run the stories through all of the criteria we had developed as a team earlier in the process.”

Joan added, “Our purpose was not only developing material for our learners, but also to create exemplars to demonstrate to instructors what they needed to take into consideration when they were developing [their own] materials.”

As part of the project, they reviewed other initiatives and related research to gather information about best practices in developing reading materials for new readers. They discovered ongoing work being done in this area at Newcastle University in England. Researchers Young-Scholten and Maguire (2010) found that there was a shortage of non-fiction and fiction books written for the lowest level second language learners. They set up a pilot project to train undergraduate English language and linguistics students to write stories for low level ESL literacy learners. The purpose of their project was two-fold: to educate the student writers about the needs of low literacy English language learners and to increase the availability of books for this population. The pilot eventually led to the Cracking Good Stories project, an ongoing initiative that trains people on how to write books for low literacy ESL learners and contributes to the development of appropriate level books for this learner group.

As part of the project, they reviewed other initiatives and related research to gather information about best practices in developing reading materials for new readers. They discovered ongoing work being done in this area at Newcastle University in England. Researchers Young-Scholten and Maguire (2010) found that there was a shortage of non-fiction and fiction books written for the lowest level second language learners. They set up a pilot project to train undergraduate English language and linguistics students to write stories for low level ESL literacy learners. The purpose of their project was two-fold: to educate the student writers about the needs of low literacy English language learners and to increase the availability of books for this population. The pilot eventually led to the Cracking Good Stories project, an ongoing initiative that trains people on how to write books for low literacy ESL learners and contributes to the development of appropriate level books for this learner group.

Incorporating this and other research with the experience of practitioners working in the CEIIA, Theresa and Joan compiled a list of best practices for practitioners to consider in the creation of their own ESL literacy stories, which is included in the ESL Literacy Readers Guide that was written as an accompaniment to the readers:

- Choose relevant themes. Learners will understand and better relate to stories that speak to their everyday lives.

It’s so important that the reading material we’re giving our learners to work with is something that is completely relevant, that they can connect to, that has to do with their day-to-day lives, or something that they already have experience with so that the text doesn’t become cumbersome. They are learning to read, learning the reading strategies, learning the vocabulary, learning the syntax, and so adding an unfamiliar topic that potentially has little relevance to the learners’ lives does not support the reading process,” Theresa explained.

- Keep vocabulary simple. Stories should consist of vocabulary familiar to learners; only a few new words should be introduced in a reading. Repetition of key words is critical, particularly with lower Canadian Language Benchmark (CLB) levels.

“Learners have to be able to read 98% of the surrounding text before they’re able to use context clues so that’s a very high percentage of words that they have to be familiar with in order to use that strategy. I think that’s something that often we don’t realize. It’s just too much of an overload with new words and new concepts, and unfamiliar situations or unfamiliar content. That whole scaffolding piece before they actually get to reading the text is so critical. Whether that’s oral language or work with the new vocabulary and different kind of games and that sort of thing. We need to set them up for success,” Joan emphasized.

- Choose fonts carefully. Font type and size are both important. Fonts should be clear, easy-to-read, and larger than in non-literacy materials. At the lower CLB levels, the font used should not contain the script version of ‘a’; however, it should be introduced in the higher levels as it is found in most authentic print.

- Include plenty of whitespace. An uncluttered page is critical in stories written for LIFE (learners with interrupted formal education). The amount of whitespace can decrease with higher CLB levels.

- Use authentic pictures. Good pictures facilitate comprehension a great deal. The more realistic the pictures are, the more easily learners will interpret them – a photograph is better than a drawing, for example.

(Bow Valley College 2011, 10)

After doing this project, I have a new awareness of how complex the process of reading text is, and what you need to take into account to come up with texts that are meaningful, relevant, level appropriate, and address the learner’s reality. (Joan Bruce, ESL literacy practitioner, personal interview)

The ESL Literacy Readers Guide is intended to assist practitioners in developing lessons for both the pre-reading and post-reading stages. It explains how the 40 stories are organized in levels from introductory to intermediate, and encompass the range of reading skills within each level.[2]

It also explains the importance of themes, and how they were carefully selected in the writing of the stories and recur throughout the different levels. “Theme-teaching allows for a natural progression into practical, real-life extension activities – activities that go beyond the classroom and have a basis in authentic printed material and application in the community” (ESL Literacy Readers Guide 2011). The guide gives suggestions for extension activities corresponding to the themes and using authentic printed materials. Theme topics include food/shopping/money, housing, transportation, employment, leisure, health, school and clothing.

Both the Readers’ Guide and the Readers themselves are freely available and easily downloaded from the ESL Literacy Network.

I asked both Theresa and Joan about the success of the ESL Literacy Readers. Were learners using them and had they improved their skills?

Theresa replied, “I remember one of the things I was excited about was that one of the learners in our class told me she was actually reading her book at home. She had it in her bedroom so when she put her child down to sleep, she’d make some time to read. To me, there were two important pieces to this – first, there was a book she could (and wanted to) read independently, and second, this book was hers to keep and read whenever she wanted to. Now she had the tools to practice reading at home on her own.”

Joan added, “We sometimes also don’t realize the importance of a child seeing their parent read. That it is sending a message to the child that reading is important and that it’s something we enjoy doing. And so having this woman able to read to her child or having books in the home, the effects of that are far reaching because it affects the child and their attitude, and how they feel about reading.”

Some final words

The ESL Literacy Readers project is successful and innovative on many fronts. The Canadian-produced materials are specifically designed and written with the needs of adult ESL literacy learners in mind. The chosen themes are of high interest and pertinent to learners’ lives. The events and issues portrayed are those that a typical learner may experience in their new country. Deng goes to school, Lien buys food, Amir gets sick, and A Problem at Work are only a handful of titles in the 40 stories. An added bonus is that the photos accompanying the stories are of learners at Bow Valley College. Research and experience has shown that the more realistic a photo is, the more easily learners will interpret them and relate to them. The ESL Literacy Readers fill an important need for relevant, interesting adult-oriented reading materials targeted at beginning ESL literacy learners.

This project made it possible for instructor-created materials, developed specifically for ESL literacy learners, to be available to instructors across the country. And for learners to be able to take home and keep these books is a big deal for someone who has not had access to books that are both level appropriate and age-appropriate. (Theresa Wall, ESL literacy practitioner, personal interview)

References

Bow Valley College. 2011. ESL Literacy Readers’ Guide. Calgary: Bow Valley College, ESL Literacy Network. https://esl-literacy.com/readers/esl_literacy_readers_guide.pdf

Bow Valley College. 2011. ESL Literacy Readers. Bow Valley College, ESL Literacy Network. https://esl-literacy.com/readers

Clarity, Mary. 2007. “An Extensive Reading Program for Your ESL Classroom.” The Internet TESL Journal 13(8). http://iteslj.org/Techniques/Clarity-ExtensiveReading.html

Maley, Alan. 2009. “Extensive reading: why it is good for our students…and for us.” Teaching English Blog (British Council, BBC World Service). https://www.teachingenglish.org.uk/article/extensive-reading-why-it-good-our-students%E2%80%A6-us

Smith, John W. A. and Warwick B. Elley. 1997. How Children Learn to Read: Insights from the New Zealand Experience. Auckland, New Zealand: Longman.

Young-Scholten, Martha and Margaret Wilkinson. 2010. “The Cracking Good Stories project: Creating fiction for LESLLA adults.” Presented at the EU-Speak Inaugural Workshop, Newcastle, England, November 5-7.

[1] LINC refers to Language Instruction for Newcomers to Canada, a program funded by the Government of Canada (http://www.cic.gc.ca/english/department/media/backgrounders/2013/2013-10-18.asp).

[2] The Canadian Language Benchmarks 2000: ESL for Literacy Learners document informed the development of the ESL Literacy Readers (http://www.language.ca/documents/e-version_ESL_Literacy_Learners_April_2010.pdf). This document organized the different ESL literacy levels into phases. It has since been revised, and the organization changed from phases to levels (Canadian Language Benchmarks: ESL for Adult Literacy Learners (ALL), http://www.language.ca/documents/CLB_Adult_Literacy_Learners_e-version_2015.pdf). In the near future, the ESL Literacy Readers will be re-organized to reflect the levels outlined in the 2015 document.

___________________________________________________________________

One Size Does Not Fit All: Designing Curriculum and Assessment for Adult ESL Literacy Learners

Published Dec 4, 2015

Developing “pathways, programming, services, and curricula design that promote a highly flexible, interactive and supportive environment” for learners is one of Bow Valley College’s Vision 2020 priorities (Bow Valley College 2011b, 15). Learning for LIFE: An ESL Literacy Curriculum Framework embodies this principle, and extends it beyond the walls of the College by supporting organizations to create their own customized curriculum tailored to their communities’ and their learners’ needs. “Curriculum is both planned and lived (Aoki, 2005). The planned curriculum is the formalized curriculum which is developed in response to an understanding of the needs of learners as a group, the needs of your community and the wider environment of which your program is a part. The lived curriculum is the way in which the planned curriculum is addressed in the classroom, as instructors respond to the needs, interests and learning styles of individuals. Understanding curriculum as lived is one way of acknowledging ‘the uniqueness of every teaching situation’ (Aoki, 2005, 165).” (Bow Valley College 2011a [Framework], Introduction, 7).

“Curriculum is both planned and lived (Aoki, 2005). The planned curriculum is the formalized curriculum which is developed in response to an understanding of the needs of learners as a group, the needs of your community and the wider environment of which your program is a part. The lived curriculum is the way in which the planned curriculum is addressed in the classroom, as instructors respond to the needs, interests and learning styles of individuals. Understanding curriculum as lived is one way of acknowledging ‘the uniqueness of every teaching situation’ (Aoki, 2005, 165).” (Bow Valley College 2011a [Framework], Introduction, 7).

ESL literacy learners bring diverse strengths and challenges into the classroom. Their life experiences may include war, poverty, and other forms of violence and trauma. Their formal education has been limited or interrupted for many reasons.

As a result of this history, many ESL literacy learners have not developed “the knowledge, skills and strategies that are commonly assumed of adults in Alberta” (Framework, Stage 1, 6). However, they possess remarkable resilience, survival skills, and perseverance. They are genuinely motivated to learn English language and literacy skills so they can participate as full citizens in their new lives in Canada.

This struck me from the very first day I walked into an ESL literacy classroom. As much as possible, leave your assumptions at the door. You don’t really know what people’s backgrounds are, what their skills are, what might be scary for them, or what might be comforting for them. (Katrina Derix-Langstraat, ESL literacy practitioner, personal interview)

Early in 2009, the Centre for Excellence in Immigrant and Intercultural Advancement (CEIIA) at Bow Valley College, with funding from the Alberta Government, began developing a curriculum framework intended to provide information, guidance, and a structure that would help adult ESL literacy program administrators, curriculum developers, and practitioners develop responsive programs designed to meet the specific needs of their distinct  learners. It was not a “one size fits all” approach, which would be inappropriate and ineffective given that ESL literacy programs are diverse – in location (urban/rural), setting (colleges, community organizations), and learners. Instead, it aimed to provide a thoughtful and considered framework that encouraged practitioners to engage in their own curriculum planning process. Katrina Derix-Langstraat (project lead) and Jennifer Acevedo (project consultant) talked with me about how the Learning for LIFE: An ESL Literacy Curriculum Framework took shape.

learners. It was not a “one size fits all” approach, which would be inappropriate and ineffective given that ESL literacy programs are diverse – in location (urban/rural), setting (colleges, community organizations), and learners. Instead, it aimed to provide a thoughtful and considered framework that encouraged practitioners to engage in their own curriculum planning process. Katrina Derix-Langstraat (project lead) and Jennifer Acevedo (project consultant) talked with me about how the Learning for LIFE: An ESL Literacy Curriculum Framework took shape.

Katrina began. “The curriculum framework was one stage of a larger project. The other parts were the Learning for LIFE: An ESL Literacy Handbook and the ESL Literacy Network website. The intention was to create a resource that would help programs across the province to develop an ESL literacy curriculum of their own. The resource is intended to support both classroom instructors and program developers. It was meant to give them a place to start.”

The Framework project began with an extensive review of the research and theory in adult ESL literacy and adult first language acquisition. This process also included a review of curricula and curriculum framework models from a variety of resources and countries.[1]

Katrina and Jennifer took a collaborative approach in developing the resource. The Framework project included the formation of an Alberta Advisory Committee comprised of ESL literacy experts and practitioners. This committee provided ongoing feedback throughout the project. Interviews and site visits were conducted at community and educational organizations throughout rural and urban Alberta. As well, experienced ESL literacy practitioners at Bow Valley College contributed their collective expertise and insight.

“There were consultations with different programs and providers across the province. We discussed learner demographics, the learning needs of the learners, as well as practitioners’ perceptions about those needs. These conversations helped to identify emerging themes and trends,” Katrina explained.

Through their research and consultations, Katrina and Jennifer outlined four program contexts of ESL literacy programming for the Framework:

Community orientation and participation in ESL Literacy programs: These programs focus on addressing needs related to the acclimatization stage of the settlement continuum.

Employment ESL literacy programs: These programs provide ESL literacy for the workplace or ESL literacy in the workplace.

Family ESL literacy programs: These programs focus on providing ESL literacy development for parents and children, and also often address parenting skills.

Educational preparation ESL literacy programs: These programs aim to transition learners from ESL literacy to adult basic education programs or other training opportunities.

(Framework, Stage 1, 15)

Learning for LIFE: An ESL Literacy Curriculum Framework provides background information and guiding principles for all four of these program contexts and can be easily adapted according to a program’s needs and resources.

Katrina elaborated on the stages of curriculum development. “We came up with a five-part process. Stage1 is understanding needs, both the community’s needs and the learners’ needs. Stage 2 is determining the focus of your program. Stage 3 is about setting learning outcomes. Stage 4 is about integrating assessment for learners. Stage 5 is demonstrating accountability to all stakeholders. It’s not intended to be a linear process. The parts influence each other and there is interplay back and forth. However, if you’re going to design a program, or even as an instructor, these are things you need to think about, and then make decisions based on your learners, your demographics, and what’s possible in your context. It’s not ‘here we did it for you.’ People still need to do a lot of work on their own.”

The Framework also looks at Habits of Mind. Katrina explained, “Habits of Mind are the soft skills, the non-literacy skills that learners need to be successful in school. They are things like setting goals, managing your learning, being prepared for different situations, managing information, and managing your time.” Jennifer added, “Based on conversations with other practitioners, we heard that learners don’t often realize how their behaviour is perceived. We do them a disservice if we don’t try to illuminate aspects of Canadian culture such as expectations at school or at work. We tried to develop a process, a series of questions teachers could draw upon in their classrooms.”

“In the Framework, Habits of Mind is the term used to describe the non-literacy skills that demonstrate the characteristics of successful learners in North American contexts” (Framework, Stage 3, 94). The term draws on the research of Costa and Kallick that identified 16 Habits of Mind[2] that contribute to success in learning and in life. They defined a habit as a behaviour that requires “a discipline of the mind that is practiced so it becomes a habitual way of working toward more thoughtful…action” (Costa and Kallick 2008, xvii).

The Framework focuses on four specific Habits of Mind: resourcefulness, motivation, responsibility, and engagement (Framework, Stage 3, 96). For each of the four, the Framework provides a description of the Habit, a description of the skills that support learners in demonstrating the Habit, considerations for understanding learners’ challenges, considerations for building on learners’ strengths, and a process of skill development that demonstrates each Habit of Mind (Framework, Stage 3, 99). In addition, practitioners are given considerations for assessing these Habits of Mind (Framework, Stage 4, 51-52).

The Importance of Integrating Alternative Learner Assessment

Katrina talked about the importance of assessment. “It’s particularly challenging in this field to make assessment meaningful, purposeful, and transparent. We want to demonstrate accountability to learners and instructors, and to the other stakeholders [funders, administrators]…. One of the reasons we included Habits of Mind is that progress is gradual depending on the learner’s background knowledge and life experiences. We see great growth and progress in learners over the course of a term or a program in these other [soft skill] areas which actually have a huge positive impact on learning…. So including Habits of Mind gave instructors some language and some awareness to capture the progress being made in [these soft skills], because everything, like bringing your glasses to school and knowing when it is appropriate to speak out…makes students more aware of themselves as learners.” Jennifer added, “The learners have an opportunity to practice these skills and make connections with their previous experience…and these skills help them succeed in their daily lives…how to be a student, how to be an employee….”

“Assessment is a transparent, ongoing process of purposefully gathering useful information that directs instruction and enables communication about learning. Effective assessment provides detailed, useful information for instructors, learners and other stakeholders” (Framework, Stage 4, 4). The Framework recommends getting learners involved in the assessment process by:

- using assessments for different purposes,

- integrating informal assessment as part of the classroom routine,

- using a portfolio based language assessment approach, and

- integrating regular learning conferences [with learners] as an opportunity for communicating about learning expectations, challenges and achievements. (Framework, Stage 4, 6)

The Framework’s philosophy surrounding assessment is congruent with a formative assessment model that requires learners’ engagement and involvement. Practitioners do not just give feedback but engage in a dialogue with students about learning.[3]

Progress for ESL literacy learners is not always straight-forward or linear. The more complex and flexible measurements of success such as personal growth, self-confidence, independence, social connections, and changed attitudes toward life and learning are all ways to measure progress, but are not easily quantified or standardized. Building accountability into each stage of curriculum development helps demonstrate and value the incremental progress made by ESL literacy learners.

Developing skills and personal growth are inextricably linked and equally necessary for foundational learners to make progress. Learners develop skills when they have the self-confidence to take risks and when the experience themselves as learners. They build self-confidence and experience themselves as learners when they develop skills that make a difference in their daily lives at work, at home, and in the community. Including both these components of progress offers the possibility of honouring the whole learner and giving a true indication of progress. (Jackson and Schaetti 2014, 54)

A Success Story

Jennifer shared a successful application of the Framework within her own work. “I took the Curriculum Framework that we designed and used it to successfully create and pilot a curriculum for what we call our ‘Practical Program’ at Bow Valley College. We define ‘practical’ learners as learners with 4 to 9 years of education who already have the very basics of literacy but still need support to develop more learning strategies and literacy skills. These learners benefit from a program designed for their specific needs.”

“The development of the Practical Program curriculum was a huge undertaking as the program consists of nine levels. The curriculum provides instructors with a progression of connected outcomes over these nine levels. The outcomes help instructors measure learners’ progress in small incremental steps across the levels, allowing for spiralling and recycling. Without the Curriculum Framework to support the development of this curriculum, it would have been much more of a challenge to create it. The Curriculum Framework provided a structure and tangible outcomes, not only in reading, writing, listening, and speaking, but in learning strategies and life skills as well. The result is a program curriculum that is able to effectively address the literacy and language needs of learners. Instructors use the Practical Program curriculum for planning, teaching, and assessment, providing learners with a cohesive learning experience across all levels of the program.”

Final Words

Learning for LIFE: An ESL Literacy Curriculum Framework is the culmination of well-considered research and the collective expertise of experienced ESL literacy practitioners. It provides an invaluable resource to ESL literacy program administrators, curriculum developers, and practitioners as they engage in the dynamic and ongoing process of developing responsive ESL literacy programming tailored to their learners’ needs.

An effective curriculum is responsive to learner needs and reflects the context in which it operates. Adult ESL literacy programs in Alberta are diverse, serving different learner populations in both urban and rural contexts, in part-time and full-time settings. The ESL Literacy Curriculum Framework addresses this diversity by provided a general process for curriculum development, as well as information for specific program contexts. (https://esl-literacy.com/curriculum-framework)

References

Aoki, Ted T. 2005. “Teaching as In-dwelling Between Two Curriculum Worlds (1986/1991).” In Curriculum in a New Key: The Collected Works of Ted T. Aoki, edited by William F. Pinar and Rita L. Irwin, 159-165. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Bow Valley College. 2011a. Learning for LIFE: An ESL Literacy Curriculum Framework. Calgary: Bow Valley College. https://esl-literacy.com/curriculum-framework

Bow Valley College. 2011b. Vision 2020: Learning Into the Future. A Report to the Community. Calgary: Bow Valley College. http://web.bowvalleycollege.ca/pdf/BVCVision2020Report2011.pdf

Costa, Arthur L., and Bena Kallick (Eds.). 2008. “Describing the Habits of Mind.” In Learning and Leading with Habits of Mind: 16 Essential Characteristics for Success. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development. http://www.ascd.org/publications/books/108008/chapters/Describing-the-Habits-of-Mind.aspx

Derrick, Jay, Kathryn Ecclestone, and Juliet Merrifield. 2007. “A balancing act? The English and Welsh model of assessment in adult basic education.” In Measures of success: Assessment and accountability in adult basic education, edited by Pat Campbell, 287-323. Edmonton: Grass Roots Press.

Jackson, Candace, and Marnie Schaetti. (2014). Research Findings: Literacy and Essential Skills: Learner Progression Measures Project. Calgary: Bow Valley College. https://centreforfoundationallearning.files.wordpress.com/2013/10/lpm-researchfindingsreport.pdf

[1] The Manitoba Adult EAL Curriculum Framework Foundations: 2009 and the Massachusetts Adult Basic Education Curriculum Framework for English Speakers of Other Languages (2005) were influential in developing the resource.

[2] “The Habits of Mind are an identified set of 16 problem solving, life related skills, necessary to effectively operate in society and promote strategic reasoning, insightfulness, perseverance, creativity and craftsmanship.” (http://www.chsvt.org/wdp/Habits_of_Mind.pdf)

[3] Researchers Derrick, Ecclestone, and Merrifield (2007) list ten best practices in formative assessment:

- Make it part of effective planning for teaching and learning, which should include processes for feedback and engaging learners.

- Focus on how students learn.

- Help students become aware of how they are learning, not just what they are learning.

- Recognize it as central to classroom practice.

- Regard it as a key professional skill for teachers.

- Take account of the importance of learner motivation by emphasizing progress and achievement rather than failure.

- Promote commitment to learning goals and a shared understanding of the criteria being assessed.

- Enable learners to receive constructive feedback about how to improve.

- Develop learners’ capacity for self-assessment so that they become reflective and self-managing.

- Recognize the full range of achievement for all learners.

________________________________________________________________

Financial Literacy Month

November is Financial Literacy Month (FLM)[1] and this year’s theme is “Count me in, Canada”, emphasizing the fact that building financial literacy in Canada depends on the involvement and collaborative efforts of the public, private, and non-profit sectors. The first Financial Literacy Month was launched in 2011 with the Financial Literacy Action Group to raise awareness among Canadians about the importance of financial literacy in strengthening an individual’s financial well-being. The purpose of FLM 2015 is to bring organizations and individuals across Canada together to support the National Strategy for Financial Literacy – Count Me In, Canada, which was introduced in June 2015. The strategy’s three goals are to help Canadians:

- manage money and debt wisely,

- plan and save for the future; and

- prevent and protect against fraud and financial abuse.

(Financial Consumer Agency of Canada 2015)

This article in the Stories from the Field series celebrates innovative and responsive financial literacy programming developed by the faculty in the Centre for Excellence in Immigrant and Intercultural Advancement (CEIIA) at Bow Valley College. Read on to learn more.

Innovative Financial Literacy Programming Helps Newcomers Navigate Canada’s Financial Landscape

Published Nov 12, 2015

I enter an English language learning classroom at Bow Valley College that has been rearranged to look like a classic science fair. The energy and excitement is palpable. Groups of three or four learners are gathered around half a dozen tables. On each table is a tri-fold display, and I catch glimpses of some of the headings: Banking, Saving and Investment, Entrepreneurship, Shopping Wisely. In the classroom across the hall, clusters of two and three learners are gathered around laptop computers participating in PowerPoint presentations on topics related to money and finances. As I walk from table to table, listening to the different presentations, I learn about debt, savings, starting a new business, bank accounts, automated banking machines, budgeting, and the least expensive grocery store (as identified by Bow Valley College ESL learners).

It’s the third annual Financial Literacy Fair hosted by ESL learners in the Bridge and the Youth in Transition (LINC) programs. Both programs serve young adult immigrant learners ages 18 to 24. The students have worked for weeks to prepare for this day.

It’s the third annual Financial Literacy Fair hosted by ESL learners in the Bridge and the Youth in Transition (LINC) programs. Both programs serve young adult immigrant learners ages 18 to 24. The students have worked for weeks to prepare for this day.

Research shows that for newcomers, financial literacy is an essential skill for creating a successful life in Canadian society. Research also indicates that financial literacy may be a challenge for many newcomers along with the other settlement concerns they face.

What do we mean by financial literacy?

“Financial literacy means having the skills and knowledge to use money wisely. Being financially literate means having the knowledge to make prudent financial decisions, now and for the future” (Bow Valley College 2010b, 1).

Studies have shown that “upon arrival, and during the first year of settlement, the probability of entering poverty is high among newcomer populations (34% – 46%) and this tendency seems to be increasing. Statistics show that approximately 65% of immigrants experience bouts of low income within the first 10 years in Canada” (Picot, Hou, and Coulombe 2007, cited in SEDI 2008, 3).

While low income is not always connected to low financial literacy, newcomers without access to financial literacy supports are “at greater risk of slipping into further poverty” (SEDI 2008, 3).

Despite the government’s renewed focus on increasing financial literacy for all Canadians, newcomers continue to face unique challenges that require not only innovative and responsive programming, but policy changes within government and financial institutions.

Prosper Canada Centre for Financial Literacy[2] is on the steering committee of the Asset Building Learning Exchange (ABLE), a “national coalition of community practitioners, financial institutions, researchers, policymakers, and funders committed to advancing financial empowerment approaches to improve the financial capability and wellbeing of Canadians living in, or at high risk, of poverty” (ABLE 2014, 1). In a research brief prepared as part of a response to the government’s National Strategy, ABLE identifies some of the systemic and other financial literacy barriers newcomers may experience:

- public policies/programs that impede positive financial behaviours by people living in low-income (e.g., savings and asset restrictions for social assistance and disability benefit recipients) or fail … to incentivize them to the same extent as other citizens;

- reliance on unstable, low-wage jobs and other forms of precarious employment;

- reluctance to access mainstream financial institutions by those who have had negative experiences with financial institutions, either in Canada or in their country of origin;

- complicated application procedures or lack of clear messaging about eligibility requirements for tax credits and other public benefits to which they are entitled;

- low levels of literacy and/or numeracy; and

- limited knowledge of English and/or French.

(ABLE 2014, 2-3)

In addition, newcomers face unique financial pressures including “financial responsibility for family members in Canada and/or their country of origin; failure to recognize foreign credentials, leading to difficulties securing adequate employment; and the financial burden of repaying refugee transportation loans, relative to typically low levels of income” (ABLE 2014, 5-6).

Financial institutions, community-based organizations and other agencies and individuals who assist newcomers during their initial adjustment period must rise to the challenge and work together to improve the availability of programs and materials that respond to immigrants’ specific needs. (Lutheran Immigration and Refugee Service 2012, 22)

The Financial ESL Literacy Toolbox: An Innovative response to increasing financial literacy among newcomers

This brings us full circle to the Financial Literacy Fair at Bow Valley College. Ruby Hamm and Heidi Beyer are part of the faculty in the Centre for Excellence in Immigrant and Intercultural Advancement (CEIIA). They work with young adult ESL learners helping them to develop their reading, speaking, listening, communication skills, and essential skills – including numeracy. Their programs include a focus on the development of financial literacy skills. The Financial Literacy Fair showcases learners’ understanding and comprehension of financial literacy concepts taught throughout the trimester. I spoke with Ruby and Heidi to learn more about this important topic.

Ruby began our conversation by explaining that “in the Youth in Transition program, the end of trimester project this past spring was to host a financial literacy fair for the rest of the young adult immigrant population at the College.”

Heidi described how it comes together. “We have a number of different stations [depending on class size] so some learners are presenting on how to manage a budget and showcasing Microsoft Excel while others are presenting on the use of credit cards, and some learners are presenting on saving money. The students have to build up their own expertise, not only during class time, but out of class as well. They have to go out into community to get information, bring it back, synthesize it, figure out how to explain it to their peers, come up with takeaway information that people can take home, and be prepared to answer any questions. They know learners visiting the fair will have a lot of questions because financial literacy is an area where they have gaps in knowledge.”

For instructors and learners alike, the annual Financial Literacy Fair is a highlight of the school year. The financial literacy learning doesn’t stop there. Heidi and Ruby are also co-collaborators and developers of the Financial ESL Literacy Toolbox, a compilation of innovative resources that practitioners can use to teach financial literacy.

Funded by the Alberta Government, the Toolbox was developed to meet the needs of ESL literacy learners. Specifically, the resource is intended “to support learners with interrupted formal education (LIFE) who are at risk of not completing high school education and transitioning into post-secondary studies or career programs” (Bow Valley College 2010a, 1).

Heidi described the project this way: “Before we started creating the resource, we did a landscape analysis. We realized that not many of the tools we could find were for ESL literacy learners. None of the tools would have worked without being adapted in some way for the classroom so I think that was very much kind of a driving force behind this project. At the end of this project, the Toolbox reflects the collective knowledge of ESL literacy practitioners at Bow Valley College, and provides other practitioners across the country with peer-reviewed lesson plans developed for various literacy levels.”

Ruby shared how they started out in the process to develop the Toolbox. “We got together in early 2009 and started talking about what is it that learners need in order to be successful financially, in order to be able to deal with money in a way that’s really going to move them forward. And we didn’t just talk about it ourselves, we were able to talk with several focus groups. We brought in ESL literacy instructors that taught from beginner to more advanced levels, and asked them, ‘What is it that your learners really need?’ … And we were able to take that information and then decide, okay this is the direction that we need to go with our Toolbox.”

Heidi added, “Not all numeracy gaps can be addressed in classrooms that focus on language development. However, there are some core skills and knowledge that you need to know about money and how to navigate financial systems here in Canada. Fundamentally, we’re ESL literacy practitioners – we’re not math instructors. So our challenge was how do we build a Toolbox that enables a non-math teacher to introduce a numerical concept? We wanted to use what we know is best practice for this audience [practitioners].”

Heidi and Ruby worked together with instructors and learners in the CEIIA to identify gaps in numeracy skills and to develop financial knowledge relevant to the Canadian context. They were grateful that as practising instructors, they could try the new resources out in the classroom and use feedback from the learners to inform the shape and design of the Toolbox.

Ruby highlighted a strength of the Toolbox. “One of the things we did was look at the Alberta curriculum to see what numeracy skills could be taught in the context of financial literacy. Literacy learners don’t necessarily understand numeracy. They may not have a math background so financial literacy concepts may be used to teach the math. For example, decimals can be better understood in the context of money. That way the teaching enhances the understanding of money and of decimals. We worked to ensure that there were connections. In the Toolbox, the financial literacy outcomes and the numeracy outcomes are both present and connected.”

As well as learning a new language and navigating educational pathways, our learners are keen to learn how to make money work for themselves, their families and learn how to make wise financial decisions today and in the future. (Bow Valley College 2010a, 1)

The Toolbox has been highly successful in helping learners understand the meaning of money and move forward financially. Heidi and Ruby shared some success stories.

Ruby recalled, “We were working with a calculator online and I showed a student how to use it. He was a smoker and he started figuring out how much his cigarettes cost and he started plugging in the numbers. He said, ‘Ohhhh, if I quit smoking I could have a car.’ I said, ‘That’s right.’ You know, it’s as simple as that. You need to use your money differently.”

Heidi gave other examples. “The class was learning about budgeting skills. We had built our vocabulary about incoming and outgoing funds and we actually connected it to using Microsoft Excel. And I had one learner who just, wide-eyed, kind of shot up out of her seat and said, ‘I don’t make that much money.’ They had been collecting their receipts in an envelope. And she literally was plugging them into this spread sheet, and she had no idea. That was the first time she made that connection that she was spending more than she actually made. Another learner who worked in a restaurant was walking past her manager’s office, and her manager was struggling with how to make a pie chart in Microsoft Excel. She said, ‘Oh I think I can help you with that,’ and she went in and did it. She stopped working in the restaurant and was promoted to working in the office. Another higher level learner went into the bank with her parents and helped them get a mortgage because she knew where to get her information, she knew the questions to ask, and she understood how the interest would be calculated.”

The Toolbox has been well received locally, provincially, and nationally. To encourage use, the resources are easily accessible on the Financial ESL Literacy Toolbox website, which is part of the ESL Literacy Network, and can be downloaded and adapted to suit diverse learner needs.

Heidi described the reach of the project. “I’ve done numerous presentations on the Toolbox and financial literacy including for Alberta Teachers of English as a Second Language (ATESL) and hosted webinars on the ESL Literacy Network. I was invited to speak with the Further Education Society of Alberta as part of their practitioner training to do a really hands-on workshop to get them started and ready to jump in to teaching financial literacy. ESL organizations from across the country are recognizing the need for financial literacy instruction and have turned to the CEIIA to access support with material and curriculum development.”

The Case for Financial Literacy – Some final words

The financial literacy field has begun to articulate some guiding principles for effective financial literacy interventions aimed at vulnerable groups. In a research report for the Canadian Centre for Financial Literacy, Robson found that financial literacy interventions are most effective when they:

- offer appropriate, accurate content, tailored to the audience;